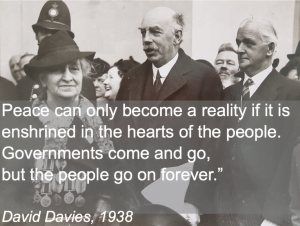

David Davies 75: Internationalist ‘Father’ of the Temple of Peace

By Craig Owen, Head of Wales for Peace at WCIA

On June 16th 2019 – appropriately enough, Father’s Day – it was 75 years to the day since Lord David Davies of Llandinam (1880-1944), father and founder of Wales’ Temple of Peace & Health, passed away. A leading thinker in Welsh internationalism who left his mark on the nation in a myriad ways, he died just months before the end of the World War that he had campaigned to avert, and on the verge of the creation of the United Nations that he had worked towards for 25 years.

This article was written by Temple of Peace Heritage Coordinator Craig Owen to mark the 75th Anniversary of his passing, and was the basis for Craig’s Gregynog Festival Lecture on June 19 2019 – also marking the centenary of the post-WW1 Treaty of Versailles. Craig continues to research the History of Welsh Internationalism, and following original publication of this piece, David Davies life has been researched by Aberystwyth History postgraduate Ewan Lawry, whose podcast can be heard below.

David Davies’ Legacy

David Davies is a legendary figure to many generations who have worked, met, campaigned and volunteered at Wales’ Temple of Peace and Health in Cardiff since its opening in 1938. His name is also immortalised in the David Davies Memorial Institute, which resides at the world’s first Department of International Politics which he founded at Aberystwyth University in 1919 – this year celebrating its centenary – and in the David Davies Llandinam Research Fellowship at LSE. In 1910 he established the (King Edward VII) Welsh National Memorial Association (WNMA), with the aim of eradicating Tuberculosis and advancing Public Health. It became one of the founding bodies of the Welsh National Health Service (NHS) in 1946-48 – which operated from the Temple of Peace and Health. David Davies was also instrumental in founding the Welsh National Agricultural Society (now the Royal Welsh) in 1904; in establishing National Insurance with David Lloyd George in 1911, and in founding the New Commonwealth Society in 1932.

Thousands of young people continue to participate in the Boys & Girls Clubs of Wales he founded in 1928. His home, Plas Dinam, still stands sentinel over the River Severn at Llandinam in Powys, across the valley from his grandfather’s home of Broneirion – now headquarters of GirlGuiding Cymru. His sisters’ former home at Gregynog Hall, a centre for the arts and printing press since 1922 and University of Wales retreat from 1963-2013, is now in the care of the Gregynog Trust. Beyond Wales, David Davies’ internationalist ideas live on in the United Nations, the Commonwealth and in the European Union. The UN Peacekeeping force and the UN Security Council, to name but two institutions, are based directly on proposals he advocated between WW1 and WW2.

“Lord Davies was one who stood for great ideals. He had the imagination of a poet; he saw great visions. His deep sincerity, his great generosity, his burning faith made him one of those rare beings who overcome obstacles and change the course of history.” Viscount Cecil

Who was David Davies?

Oft overshadowed historically by his industrialist grandfather, also David Davies (1819-1890 – known as ‘Top Sawyer’ and builder of many of Wales’ railways, ports and coal mines), Davies was born into a ‘family of philanthropists‘ in 1880 – still firmly in the Victorian era. David attended Merchiston School in Edinburgh before reading History at Kings College, Cambridge. An avid Welsh Non-Conformist and teetotaller with a ‘roaring, infectious laugh‘, he travelled the world extensively at an early age, to Africa, Asia and the Americas – witnessing first hand the Russo-Japanese War of 1904, and owning a ranch in Edmonton, Alberta (Canada). He consequently developed a keen interest in international affairs that became his life’s passion and purpose.

In April 1910, he married Amy Penman of Lanchester, Durham and they honeymooned in East Africa. Tragically, Amy picked up an unknown disease on this trip which affected her health throughout World War One. They had two children, Michael (1915-1944) and Marguerite (1917-1930). In 1918, Amy died; David was devastated. Several years later, in 1922 he met and married Henrietta Fergusson from Pitlochry in Perthshire (with whom he had 4 more children – Mary (1923-2001), Edward (1925-1997), Islwyn (1926-2002), and Jean (1929-2011)). Henrietta became an avid supporter of David and his causes – and would go on to continue his work after his passing.

Mentored and supported by the high flying Welsh civil servant and philanthropist Tom Jones from 1910 (known as “TJ,” secretary to 4 Prime Ministers and considered one of Wales most influential political figures), David – who went by nicknames of ‘Chief‘ to his workers and ‘Dafydd Bob Man‘ to his political contemporaries – was characterised as “having boundless energy”, “thinking far ahead of his time and his contemporaries” and “churning out the work of six or eight people”. But these attributes were also his Achilles heel; Tom Jones observed that “he was impatient of contradiction or resistance to his plans; most rich young men suffer from a similar defective training. Twelve months at a desk or in a coal pit in his youth would have taught him to work with others.”

Critics remarked on Davies’ “over-confidence, impatience and intolerance for deliberation.” For his artistic and sensitive sisters Gwendoline and Margaret, he could be a pushy and challenging brother to ‘manage’, as he attempted to draw them into his many causes and projects. But Tom Jones also conceded: “only a man with his generous impulses and driving force could have overcome the obstacles in the way of (his) Associations. But… he took some managing.”

On their wealth, Trevor Fishlock – author of the sisters’ Biography – observes:

“For the Davieses, their fortunes were also a covenant. They understood very well the realities of the source of their inheritance, and of the human price of coal in the Rhondda. They felt indebted… and the immensity of their fortunes frightened them. They had seen their father devastated by anxiety over money… [and had heard their stepmother say] ‘You would never grumble about having too little money, l if you knew what it was like to have too much.'”

A Life Story yet Partially Told?

For a man of such considerable accomplishments, social and world vision, it is perhaps some surprise that no biography has yet been completed of David Davies. Until recently, his main published presence was through inclusion in E L Ellis’ ‘Biography of Thomas Jones‘. Even his Wikipedia entry is remarkably scant for a man of his achievements.

However, in 1953 the author Sir Charles Tennyson (1879-1977) – grandson of poet laureate Lord Tennyson – did indeed draft a script for a Biography of David Davies, now digitised by the National Library of Wales and publicly accessible. Sadly, this never reached publication; however, extracts were used for a smaller booklet compiled in 1995 by Peter Lewis, a Biographical Sketch of David Davies ‘Top Sawyer’ and Lord Davies of Llandinam. (reproduced from the Temple of Peace archives).

In 1963 – to mark the 25th anniversary of the opening of the Temple of Peace – John Griffiths for the BBC produced ‘One Man and His Monument‘, a radio broadcast celebrating the life of Lord Davies including interviews with many of the people with whom he had worked (and even the nurse who looked after him in his final days) – an invaluable resource and insight into the time, the script for which remains in the Temple of Peace archives today. In 2017, WCIA Volunteer Maggie Smales published a blog responding to ‘One Man and His Monument’.

‘The Peacemonger‘ feature article by J Graham Jones for the Liberal History Group (Winter 2000) offers an excellent overview of David Davies’ political and society achievements.

‘The Gift of Sunlight‘ by Trevor Fishlock, Gwasg Gomer Press, 2014 is an autobiography of David’s sisters Gwendoline and Margaret. The book beautifully interweaves their contribution to the Welsh arts with the social history of the times, illustrated with photographs and records from the family archive – including many accounts of their (sometimes challenging) relationship with older brother David and his many causes.

‘Pilgrim of Peace: A Life of George M Ll Davies’ by Dr Jen Llewellyn, Lolfa Books, 2016 is an autobiography of David Davies’ cousin, the pacifist, Conscientious Objector, peacemaker and parliamentarian George Maitland Lloyd Davies – whom David Davies’ appointed as Secretary to oversee his charities on tuberculosis (the WNMA) and housing (the Welsh Town Planning and Housing Trust).

Political Career

In the landslide election of 1906, David Davies was elected as the Liberal Party Member of Parliament for Montgomeryshire, a seat which he held until standing down in 1929.

An unconventional MP, he disliked parliamentary procedure and niceties, and regularly diverted from ‘party line’ in what he considered to be the best interests of Welsh people and world affairs. In June 1918, he sponsored a national conference in Llandrindod Wells to discuss ‘a measure of devolution for Wales‘, which went unsupported by colleagues. In 1925 – despite being the owner of the Rhondda’s Ocean Coal Company – he supported workers calling for a seven hour working day. He vehemently campaigned against the “evil spirit which appears to befog every utterance of the coal owners” and the government’s lack of conciliation surrounding the Samuel Mining Commission, seeking to involve the International Labour Organisation in averting what became the disastrous General Strike of 1926.

Despite this antagonistic relationship with political party machinery, Davies’ position in his constituency was unassailable. He was so popular, that in 1913 local Conservative press bemoaned “the cult of David Davies-ism… they have nothing in common with the ‘Radical Socialism’ which nowadays masquerades under the name of (his) ‘Liberalism.'” In present-day terms, his beliefs and interests would straddle the political spectrum: a liberal internationalist, a conservative champion of free enterprise and of hunting, and an advocate for workers rights, universal healthcare and social housing, who often spoke out against the establishment. In the context of Edwardian Empire, he was a maverick.

World War One

The outbreak of World War One in September 1914, as with every household across Wales, transformed the life and activities of the Davies family.

Initially, Davies threw his characteristic energies into recruiting and raising a battalion, the 14th Royal Welch Fusiliers (Caernarfon and Anglesey), of which he became Lieutenant Colonel. Following formation on 2nd Nov 1914 in Llandudno and rigorous training in Snowdonia, they set sail for France in December 1915, to the Western Front trenches around Givenchy.

But Davies’ experience of the trenches horrified him. On his return in 1916, he spoke in the House of Commons imploring changes in war strategy, to reverse what he saw as the “massive, appalling and needless waste of life” and the “squalor, filth and lack of supplies to which our men are subjected”.

In June 1916, David Davies was recalled to England to become Parliamentary Private Secretary to War Minister David Lloyd George, and during December 1916 Davies was one of three ‘organisers’ instrumental in mobilising support for Lloyd George to replace Herbert Henry Asquith as Prime Minister and war leader – the only Welshman to have held the UK premiership. Davies quickly became part of Lloyd George’s inner circle, regarded as a “talkative, wealthy and light-hearted young Welshman in whose friendship and gossip he took much delight at this time.”

But Davies’ experience of the trenches, and his outspokenly candid feedback to the Prime Minister on the conduct of the war effort, soon caused a rift between them. On 24 June 1917, Lloyd George dropped a bombshell of his own:

“[opponents say I am] ‘sheltering’ in a soft job a young officer of military age and fitness… In my judgment you can render better service to your country as a soldier than in your present capacity.” David Lloyd George’s dismissal note to David Davies, 24 June 1917

Top: George M Ll Davies during his military service; Gwen & Daisy nursing at the front in Troyes, France; cousin Edward Lloyd Jones, killed in action in Gallipoli, 1915.

A Dining Table and a Nation Divided

By 1917, the nation’s enthusiasm for a war ‘that should only last a few months’ had been dented by the catastrophic losses felt in every community. The Davies family represented a microcosm of the Welsh Nation – divided by war yet united in their desire for peace.

His cousin Edward Lloyd Jones had reluctantly signed up – somewhat sceptical of the war – and was killed in action in Gallipoli in August 1915. His brother Ivor Lloyd Jones was later killed in Gaza, Palestine in March 1917. Their close cousins’ deaths were felt painfully by David and his sisters.

His cousin George Maitland Lloyd Davies had initially joined the Territorial Army in 1909, but as WW1 loomed he could not reconcile the war with Christ’s teaching ‘thou shalt not kill’. Despairing at the co-option of churches and men of faith as a recruitment pulpit, he helped found Cymdeithas y Cymod, the Fellowship of Reconciliation, in 1914 – and from 1916 was imprisoned as a Conscientious Objector and opponent of the war.

David’s sisters Gwendoline and Margaret (Daisy) Davies supported the different positions their cousins had taken, as well as their brother David; but also carved their own distinct contributions to peace building in WW1. In August 1914 they organised and funded the evacuation of 91 Belgian Refugee artists and musicians to Aberystwyth on the ‘last but one boat to get away’. In 1916, they followed David to France as volunteers with the London Committee of the French Red Cross, where they set up a canteen in Troyes near the front of the Battle of Verdun, to support troops travelling to and returning from the front.

Despite his disdain for the war, David Davies remained close to and a champion of the soldiers with whom he had served in 1914-16. Two decades after WW1, he hosted a Reunion in the grounds of his home at Llandinam from 30th July – 4th August 1937, for the surviving men of his 14th Battalion of the Royal Welch Fusiliers. A Programme for the 20th Reunion Week and a Reunion Memento Booklet – recently found by Lady Davies, who made these available to WCIA for digitisation on People’s Collection Wales – captured the spirit of their Remembrance and commitment to building a better world.

“In the silent moments of our remembrance, we confronted the great phantom host which included the dearest friends of our youth. They would have become restive at the thought of what we – who know what war means – are now doing to save their dear ones from a similar fate… They say:

“What are you doing about it all? Is it to be nothing… but the laying of wreaths and blowing of last posts?”

Post-WW1: A Crusader for Peace

In August 1918 – three months before the end of WW1 – David Davies took to the stage at the Welsh National Eisteddfod in Neath, to call for the establishment of a ‘Welsh League of Nations Union‘ – even before a UK League – to harness the energies of communities Waleswide in pursuit of world peace. He was immediately supported by sign ups from the Maes and beyond:

“At the National Eisteddfod , David Davies first suggested the formation of the Welsh League of Nations Union, saying that Wales had an important role to play in the campaign for world peace. As the Union was formed in 1918 it had 3,217 members, but by 1922 this had grown dramatically to over 200,000. In 1920, Davies donated £30,000 to set up an endowment fund to establish a Welsh National Council of the League of Nations Union. By 1922 it had 280 local branches, and by 1926 the number had grown to 652.” Elgan Phillips, ‘When Aberystwyth hosted a Peace Congress‘

In 1919, David Davies and his sisters endowed the Woodrow Wilson Chair at Aberystwyth University, setting up the world’s first Chair and Department of International Politics “in memory of those students who perished in the conflict, to foster the study of the inter-related problems of law and politics, ethics and economics, raised by the project of the League of Nations.”

Although a Welsh League of Nations Union had started work in May 1920, by 1922 limited progress had been made – despite the post-WW1 clamour for peace. With his characteristic drive, David Davies in January 1922 appointed a new staff, brought in the legendary Rev Gwilym Davies as Honorary President to coordinate the league’s activities in Wales, called a founding conference in Llandrindod for Easter of 1922, and donated a £30,000 endowment fund that transformed it into one of the most influential civil society bodies in Wales throughout the 1920s.

By 1929 there were Welsh League of Nations Branches in most communities – 794 adult branches and 202 junior branches, according to the 1928-9 WLoNU Annual Report, with a combined membership of 56,606 peace campaigners. The Young People’s Message of Peace and Goodwill founded in 1922 continues to be broadcast annually today; the Women’s Peace Petition to America of 1923-4 attracted 390,296 signatories, and was presented to US President Calvin Coolidge in March 1924. In 1926, the North Wales Women’s Peace Pilgrimage saw 2,000 women march from Penygroes in Caernarfonshire to London, calling for “LAW NOT WAR.” The Welsh Education Advisory Committee, of which the Davies sisters were a driving force, had developed the world’s first ‘peace education’ curriculum “to teach the principles of the League of Nations in our schools.”

In 1926, Davies pulled off the remarkable feat of hosting the League of Nations International Peace Congress in Aberystwyth – cementing Wales’ role in the leadership of international peace building.

A full set of Welsh League of Nations Activity Reports from the 1920s and 1930s have been digitised by WCIA’s Wales for Peace project volunteers, and offer a rich source for future research into the social impact of the Union in Wales.

A ‘Temple to Peace’

Davies had originally proposed the idea of a ‘Temple of Peace’ on the site of Devonshire House in London, in 1919. However, by the late 1920s, through the peace building efforts of the Welsh League of Nations Union, he had a mass movement behind him.

During the 1920s, the Davies family had supported the creation of a Welsh National Book of Remembrance to commemorate the fallen of WW1. Serving as the roll call for the 35,000 men and women recognised by the Welsh National War Memorial – unveiled by Edward, Prince of Wales on 28 June 1928 – the book is a work of art in Moroccan leather, gilt work, vellum and mediaeval calligraphy (in the style promoted by the Gregynog Press).

Davies announced his vision for a ‘Temple of Peace’ to house the Book of Remembrance in a purpose-built crypt, and to bring together future generations to work towards building a better world of peace, health and justice in memory of the fallen. By 1929, Welsh Architect Percy Thomas had been commissioned to design Davies’ vision, and he produced full architects drawings, a detailed report and even an architects model of what would become one of Cardiff Civic Centre’s most distinctive buildings.

However, in 1930 the Great Depression hit the UK – massively affecting both construction plans for the Temple of Peace, and also the campaigning work in support of the League of Nations, which started to lose public confidence, particularly following the Manchuria Conflict of 1931. Davies, rejected as ‘visionary and impracticable’ by many colleagues, was frustrated by the readiness with which people seemed to accept the rapid deterioration in international relations and rise in militarism that followed the economic crash.

“We are prepared to die for our country; but God forbid we should ever be willing to think for it.” David Davies, 1931.

Having stepped down from Parliament in 1929, Davies worked tirelessly to reverse the tide of pessimism against the League of Nations. He founded the New Commonwealth Society, and wrote prolifically for the Welsh Outlook, Manchester Guardian and The Times, penning a number of books which remain seminal works in the field of International Relations:

- ‘The Problem of the Twentieth Century‘, 1930

- An International Police Force, 1932

- ‘Force’, 1935

- Letters to John Citizen, 1936

- ‘Federated Europe’, 1940

- The Foundations of Victory, 1941

- The Seven Pillars of Peace, 1943

“We shall never get real prosperity and security until we get peace, we shall never get peace until we get justice, and we shall get none of these things until we succeed in establishing the rule of law by means of the creation of a really effective international authority equipped with those two vital institutions, an equity tribunal and an international police force.” David Davies, ‘the Problem of the 20th Century’, 1930

In 1933, Davies’ work in peace building was recognised by the national government of Ramsey MacDonald with his elevation to the peerage, as First Baron, Lord Davies of Llandinam.

Concerned at the escalation of rearmaments by nations across Europe, Davies sponsored the tremendous ‘Peace Ballot Campaign’ of 1934-5, in which – largely due to Davies’ influence – Wales attained the 12 highest returns for the counties of the UK, with turnouts over 90% in favour of stopping the arms race that was threatening to cause another World War.

In 1934, he also stepped in to the financial ‘breach’ by giving £58,000 (£4.04 million at 2019 values) to enable construction of the Temple of Peace to proceed apace.

On April 8th 1937, Davies led the ceremony for the laying of the Foundation Stone for the Temple of Peace, alongside Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax (view photographs and press cuttings). Following an incredibly rapid but high quality construction, made possible through Davies’ ‘Sink Fund’, the Temple was readied within 18 months.

On 23 November 1938, two weeks after the 20th Armistice Day, Wales’ Temple of Peace opened to tremendous ceremony and acclaim. In another of Davies’ brainwaves – following rejection of an invitation for the young Princess Elizabeth to open the building – he felt it more appropriate that ‘the poorest wife of an ocean workman’ (coal miner) should have the honour, representing the women, mothers and wives who had lost loved ones in WW1, and led peace building efforts in the years since. The search for the ‘most tragic mothers’ of WW1 gripped the press and garnered worldwide publicity for the ceremony. Minnie James from Dowlais became the ‘mother of Wales’, opening the Temple with a golden key and leading in 20 other women from across Britain and the Empire.

- Cinereel footage from opening ceremony

- Press Pack and Photos from the opening

- Press Cuttings from the Opening Ceremony (view images here)

- ‘A New Mecca’: an Account of the Opening Ceremony

- Western Mail Souvenir supplement, 24 Nov 1937

- Collection of digitised documents from the Temple of Peace 1938 opening on People’s Collection Wales

- Blog by British Academy Fellow Dr. Emma West on rekindling ‘A New Mecca’ for today

With the benefit of hindsight, it is clear that the outbreak of World War Two in 1939 would have prevented such a project from going ahead. Without Davies’ foresight and financial intervention, the Temple – and all of the work it has gone on to do over the 80 years since – would never have reached fruition. Davies had a vision for this to be the first of a string of ‘Temples of Peace’ all around the world, mobilising civil society activism to avoid conflict and build understanding. We can only guess at what his vision might have achieved had the outbreak of WW2 not curtailed his great dream.

“I can assure you, my friends, that this building is not intended to be a mausoleum, and because at the moment dark clouds overshadow Europe and the world, that is no reason why we should put up the shutters and draw the blinds. On the contrary, in a world of madmen let us display constancy and courage. Let us as individuals and as a nation, humbly dedicate ourselves anew to the great task still remaining before us.” David Davies at the opening of Wales’ Temple of Peace

In November 2018, WCIA staged a month long programme for Temple80 and WW100, celebrating the legacy of David Davies’ remarkable monument and the movements it has inspired.

The Tragedy of World War 2

Within a year, the Temple of Peace became ‘mothballed’ with the outbreak of World War 2 in September 1939.

Whilst Davies himself was now too old to serve in the army; his son Michael signed up to the Royal Welsh Fusiliers. Davies furiously advocated for initiatives that might turn the course of the war, or ensure a robust and enduring peace on cessation of hostilities. Fearing the possibility of losing his remaining family to invasion, with great sadness – and to the great reluctance of his devoted wife, Henrietta – he arranged passage for them to live in Canada for the remainder of the war. Their home, Plas Dinam, David gave over to Gordonstoun School which relocated from Elgin in NE Scotland to Powys throughout World Warv Two.

Lord Davies – the Last Mission by H Granville Fletcher is a fascinating account of one of Davies’ ‘last ditch attempts’ to avert the conflagration of World War 2, when he travelled to Switzerland in October 1939 – following outbreak of hostilities – to persuade German industrial magnate Thyssen to cut off the supply of arms to Hitler’s armies. His mission proved unsuccessful when he discovered that Thyssen had himself fled Hitler and was a wanted man; but he made it home to the UK.

The strain of the war and separation from his family took its toll on David Davies’ health, and by 1943 he was feeling actively unwell.

The Last Picture

In February 1944, he sponsored (through his Welsh National Memorial Association at the Temple of Peace) the introduction of a fleet of mobile radiography units that would revolutionise X-Ray scanning for Tuberculosis and Cancer. Attending the launch of this cutting edge health provision at Sully Hospital, he volunteered to undergo the first scan. It picked up that he had advanced cancer of the spine. His wife and daughter were smuggled on a Navy freighter from Canada across the Atlantic, through U-Boat infested channels, to spend their final days together.

He died just four months later, on 16 June 1944, aged just 64, just 14 months before the end of World War Two. His ashes were scattered among the bracken on the hill he loved above Plas Dinam.

But David was spared the anguish of losing his son, Michael, just 3 months later. Michael Davies, who had briefly inherited the title of 2nd Baron Llandinam, was killed in action with the 6th Royal Welsh Fusiliers on 25 September 1944 during the liberation of Holland.

Working from Above

One cannot help but wonder if David Davies had been called to the ‘pearly gates’ to complete his mission from above. Within just a few years of his death, many of the causes and ideas he dedicated his whole life towards, saw fruition:

- In 1946, the newly launched United Nations Association Wales – successor to the Welsh League of Nations Union – led by Rev Gwilym Davies (in whom David Davies had placed his peace building confidence from the 1920s), organised a Memorial Service for David Davies at the Temple of Peace, and the David Davies Memorial Appeal to rebuild his peace building movement for a new, post-war era.

- 1946 the United Nations was setup – its secretariat established by Welshmen who had been contemporaries of David Davies – and his ideas became enshrined in UN Peacekeeping, in an Equity Tribunal in the UN Security Council, and in the International Educational organisation UNESCO.

- The Temple of Peace and Health would become a powerhouse for Wales’ relations with the world through the United Nations Association and (from 1973) the Welsh Centre for International Affairs, as well as International Youth Volunteering through UNA Exchange.

- In 1947 the Temple of Peace and Health also became the transitional home for the fledgling National Health Service for Wales, into which Davies’ Welsh National Memorial Association was absorbed -realising his ambition of providing universal health care to every man, woman and child. It went on to house the Glamorgan Health Board and latterly Public Health Wales.

Today, within the Temple of Peace and Health, a beautiful bronze bust of David Davies by the great 1930s sculptor Sir Goscombe John is displayed above the entrance to the Hall of Nations, accompanied by a leather bound Memorial presented to him in 1935 in recognition of his contribution to Welsh public life and his mission for peace.

But on the 75th Anniversary of his passing, perhaps the greatest legacy of David Davies is the generations of peace activists and internationalists who have been inspired by his vision to build a better world, from WW1 to today – and no doubt his enterprising spirit will continue to live on in the Temple fo Peace for future generations to come.

Find out More

Join WCIA’s ‘Peace 100’ Gregynog Festival Lecture on 29 June 2019, marking the centenary of the Paris Peace Treaty following WW1.

- Explore the David Davies of Llandinam Archives at the National Library of Wales, which also make up a key collection in the Welsh Political Archive.

- Read ‘The Gift of Sunlight’ by Trevor Fishlock, Gwasg Gomer Press, 2014

- Read ‘Pilgrim of Peace: A Life of George M Ll Davies’ by Dr Jen Llewellyn, Lolfa Books, 2016

- Read ‘Peace Profile: David Davies of Llandinam‘ by Professor W John Morgan, WISERD

About the Author

Craig Owen is Head of Wales for Peace at the Welsh Centre for International Affairs. He can be contacted on craigowen@wcia.org.uk.

Craig would like to express his gratitude to the Davies family, in particular Bea and Daniel Davies, for their inputs and permission to share David Davies’ story and materials from the family archive; and to WCIA’s Wales for Peace project volunteers and partners who between 2015-18 have gathered together the stories of Wales’ Peace Heritage.

Twitter: @WalesforPeace

Facebook: @Cymru dros Heddwch / Wales for Peace