WCIA Origins: the Campaign to Establish a Welsh Centre for International Affairs

WCIA Origins and Context

Over the course of the 1960s, the civil society bodies that had emerged from the aftermath of World War Two to shape the landscape of global activism in Wales and the wider UK –such as the United Nations Association (UNA) Wales and Council for Education in World Citizenship (CEWC) Cymru – were facing declining participation and existential challenges. The ‘great years’ of interwar mass participation enjoyed by the Welsh League of Nations Union had been heavily dependent upon philanthropists and figureheads such as David Davies; whilst where committee meetings and talks had provided a social space and meeting place for communities Wales-wide, TV ownership now connected households directly to world news.

A ‘post-Empire’ generation of hands-on activism was reflected in the emergence of International Youth Service (IYS) volunteering, Refugee Action, and Campaigns for Nuclear Disarmament and Freedom from Hunger – movements that challenged establishment orthodoxies and encouraged citizens to take action. Widespread perceptions that ever-centralising Whitehall control was ‘cutting Wales out’ of global conversations, fuelled demands for dedicated Welsh institutions; and resurgent national confidence over this period is reflected by the first devolution referendum being put to the polls at the end of the decade (which incidentally, had it succeeded, would have seen the Temple of Peace become the seat of the Welsh Assembly).

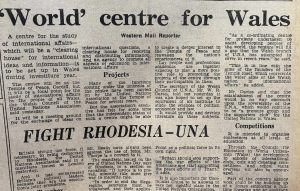

From 1968, the Western Mail pursued a 5-year campaign calling for creation of a Welsh Centre for International Affairs “to give Wales a voice on the world stage”:

“…the idea of a “Welsh Centre for International Affairs” is an exciting one… it will encourage Welshmen to look beyond the confines of Wales and Britain; to extend their knowledge and understanding of the rest of the world.” Western Mail Editorial 1968.

This impetus in Wales reflected wider trends emerging elsewhere. In his analysis of ‘the NGO Moment’, Kevin O’Sullivan argues that a ‘globalisation of compassion’ could be observed spreading world-wide from the late 1960s, as Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) simultaneously emerged to respond to perceived humanitarian need – with the Biafra Famine of 1968 the most visible trigger for widespread and spontaneous civil society response across multiple nations.

“As an expression of global compassion, NGOs borrowed from an understanding of human rights at least 2 centuries old: a vision of development and ideological continuity rooted in ‘progress’ and ‘improvement’ of Empire, to an aid industry (of post-colonial ties)…. All part of an entangled ‘history of humanitarian impulse’ that manifested in pursuit of ethical capitalism, humanitarian internationalism, refugee relief, imperial welfare, rationalised aid delivery and a broader moral economy of relief. These interwoven narratives produced a notty understanding of humanity’s obligations towards the suffering and the poor.”

Kevin O’Sullivan, ‘the NGO Moment’ (2021)

This ‘humanitarian impulse’ provides the contextual zeitgeist to what could otherwise seem the slightly random emergence of WCIA in 1973 – the only coordinating body of these 4 case studies, not to have emerged from conflict / constitutional change (the WLNU emerged from World War One; UNA Wales from Word War Two; and ‘Hub Cymru Africa’ from Welsh devolution). However, 1973 was also the height of the Cold War, the Vietnam conflict, the global oil crisis and the 3 day-week across the UK – so profound turbulence and change was in the air.

The campaign to found WCIA was formally endorsed and taken up in 1970 by the UN25 Committee, established to mark the 25th Anniversary of the United Nations under Secretary of State for Wales George Thomas MP, later Lord Tonypandy. From its first meeting in 1969, this committee set out to establish for Wales a ‘legacy for future generations’. The intent started with the idea a ‘memorial’ that would honour the post-WW2 generation’s ‘gift to the world’ of the United Nations and its Human Rights charters. The idea of an institution quickly gained fertility with the recognition that in Wales’ Temple of Peace & Health, a building and infrastructure already existed.

As an entirely voluntary (and aging) campaigning network, UNA Wales struggled to manage the Temple of Peace as a building, let alone maximise its wider potential to the people of Wales. Sharing occupancy with the Welsh Hospitals Board (itself reformed in 1973 into the South Glamorgan Health Authority), UNA themselves could see that a Welsh Centre for International Affairs could mobilise the authorities, councils, businesses, schools, and communities of Wales more profoundly than UNA alone as an explicitly campaigning, membership-based body ever could.

UNA Chairman Malcolm Pill in his 2016 memoirs describes the challenge of bringing together such a broad based instution: “the intention was an institution with charitable status which UNA, with its political aims and activities, could not attain. UNA would continue as the ‘non-charitable’; campaigning arm of the proposed centre. The project had broad and substantial support, including from academics and educators working in this field – but was vociferously opposed by a group who saw it as a betrayal of the populist campaigning tradition.”